In January 2024, Allison and I talked often about Afghanistan with a great longing to go back, but we knew it was just a dream. It was just not possible, with the current political situation, to get a visa to visit the Garden of Flowers and reconnect with the country. But still we often talked about it, wistfully and with resignation, assuming it wouldn’t happen.

In January 2024, Allison and I talked often about Afghanistan with a great longing to go back, but we knew it was just a dream. It was just not possible, with the current political situation, to get a visa to visit the Garden of Flowers and reconnect with the country. But still we often talked about it, wistfully and with resignation, assuming it wouldn’t happen.

Then suddenly, in March I was in California when I received an email from an old Italian colleague from earlier days in Kabul. She was now the head of a charity organization, and asked me if I would be interested in coordinating a program for women in southeastern provinces of Afghanistan. And I thought, wow, that sudden longing to go back to Afghanistan wasn’t without a reason, without a foundation. Just when the Taliban were increasing their draconian politics and rule in that country, at a time when feeling like going back was not an option, now here was a chance for the dream to come true, and I immediately accepted the offer – not just for the chance to go back, but also because the work I would be coordinating was so worthy and valuable, supporting livelihood development for women in rural areas who did not have a man in their family.

And so it was that at the end of August, after the tedious process of getting a visa and completing the formalities, my flight was booked to Kabul. I would fly from Munich to Dubai to Kabul, a long journey. The last leg of the journey took place in early afternoon, a three and a half hour flight from Dubai to Kabul. I was sitting by the window and looking down, and it was a sunny, beautiful day. As I looked at the land unfurling from southern Afghanistan all the way to Kabul, I can’t describe the emotions I experienced. I was deeply conscious that the geography laid out beneath me, from northwestern Pakistan to the south of Kabul (known as the Gandharaland school of art), had been the epicenter of human flourishment that gave rise to so many cultures and civilizations, including tremendous Buddhist, Hindu, and Greek art and philosophy as well as extraordinary Persian-Pushto traditions over vast centuries.

I stared down from the window of an airplane in modern times, but in my mind and with my eyes I could see the entire landscape from the past to the present, until slowly we approached modern Kabul, and trees and city buildings came into view.

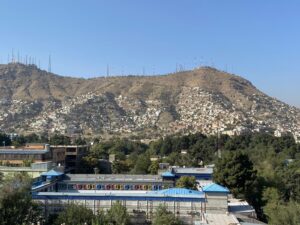

Landing in Kabul evoked an overwhelming feeling of coming back to an old memory in an old civilization, greeting again at last the country that had hosted us for several years. I reminisced about our last projects, the clinics and the House of Flowers Montessori Orphanage and thought about the Garden of Flowers Montessori Preschool, our new project from 2021, how it took off and is thriving. And now I’m coming back to work again in Afghanistan.

When we landed in Kabul, I was expecting to see a bunch of scary-looking bearded men with big turbans at passport control and Customs, but I didn’t. There were simply ordinary looking men sitting at desks. Thus my entry to the country was surprisingly unproblematic and unstressful. However, exiting a month later would reveal many more layers of security and scrutiny, let alone the many checkpoints along the way that during the month that were reminders of the hidden tight security apparatus of the Taliban. Nevertheless, the joy of coming back to Afghanistan was overwhelming.

It was even more rewarding upon coming outside where my colleagues and some old friends were waiting for me with flowers. This was a moment of very very strong joy, being welcomed back to a country that is usually perceived as hostile and fearsome.

We went into the city where I checked into a downtown hotel in the center of all activities, and I began to realize how much Kabul had changed. My last visit was in 2010. Fourteen long years had passed. During that time, so many buildings, hotels, restaurants, high-rises and wedding halls with mirrored windows had been built. This superficial appearance of gloss and growth was at first overwhelming, but then slowly as I began to settle into the city, walking back and forth from my hotel to the office daily, I gradually became reacquainted with life on the street level.  There were lots of women begging and also selling things, selling small packs of Kleenex, selling books (somehow ironic, considering that the Taliban had decided women should be minimally educated), and many little kids begging, selling chewing gum, or polishing shoes in the streets. There were definitely fewer women out in the streets than men, and those few were for the most part begging and selling. The rest were with their male company.

There were lots of women begging and also selling things, selling small packs of Kleenex, selling books (somehow ironic, considering that the Taliban had decided women should be minimally educated), and many little kids begging, selling chewing gum, or polishing shoes in the streets. There were definitely fewer women out in the streets than men, and those few were for the most part begging and selling. The rest were with their male company.

In my first days, I was not sure how to behave around women vendors and beggars, whether I could or should approach them to buy something or give them money, whether I could interact with them in public as a man. But after a day or two of careful observation of people’s behavior on the streets, I felt comfortable enough to approach some tightly veiled women carrying their babies who were selling Kleenex. My purchase was uneventful, and after that I bought Kleenex, books, fruits, nuts and whatever else any women were selling every day. My hotel room began to fill with these things I had bought on the streets. Luckily, there were never any incidents and no one stopped me or interfered when I interacted with any of the women, including those who were sitting and begging, to whom I could not resist giving money.

The streets were filled with the scent of bakeries and the smoky smell of kebab from sidewalk cafes, and one could only imagine how torturous that must have been for hungry people on the streets. Alongside the cafes were fancy restaurants and ice cream shops and fruit sellers.

The streets were filled with the scent of bakeries and the smoky smell of kebab from sidewalk cafes, and one could only imagine how torturous that must have been for hungry people on the streets. Alongside the cafes were fancy restaurants and ice cream shops and fruit sellers. I experienced a very complex flux of emotions, of joy intertwined with sadness. The joy came from being in the middle of such humble yet vibrant life; the sadness came from witnessing the despair of so many. How ambivalent life can be!

I experienced a very complex flux of emotions, of joy intertwined with sadness. The joy came from being in the middle of such humble yet vibrant life; the sadness came from witnessing the despair of so many. How ambivalent life can be!

My work involved traveling to southeast provinces, where poverty was much more obvious. People who had been kicked out of Pakistan had come back to almost nothing. Many of them lived in tents in the middle of nowhere, or had been given a temporary wooden bed in an open yard by relatives or friends. There was malnutrition and disease and infant mortality and the effects of sheer poverty that come with having no options. It was heartbreaking.

And yet, wherever we visited, immediately sweets and cookies would appear. That Afghan hospitality was the most consistent thing. They had lost everything but their dignity and their attitude of caring for guests. This dignity and hospitality epitomized a heartwarming yet invisible civilization that many old cultures in the course of history adopted, before modernity and technology hit their traditions. That flame of warmth in human interaction can outweigh any luxury in life.

This dignity and hospitality epitomized a heartwarming yet invisible civilization that many old cultures in the course of history adopted, before modernity and technology hit their traditions. That flame of warmth in human interaction can outweigh any luxury in life.

Every Saturday that I was in Kabul, I visited the Garden of Flowers. I walked across the city to get there, an hour long walk through crowded and bustling streets filled with average people. Even though the perception of Afghanistan as a terrifying place, I walked easily among people selling vegetables, men repairing motorcycles, mothers buying groceries, pharmacies selling medicines, taxis picking up passengers. I felt safe among them because they contrasted the fearsome presence of the Taliban militias with their big guns that I saw on the street corners. Among the people, fear coexisted with the normalcy of everyday life.

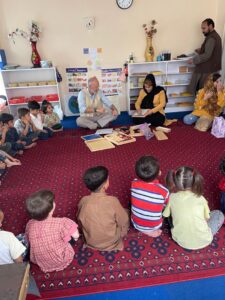

I arranged my mid-morning visits to the Garden of Flowers in time to observe the Montessori classrooms of the three teachers, Fatima, Nadia and Rohina, and their students in action. My first Saturday, I brought with me a big box of new Montessori materials donated by Allison’s friend and colleague from a Montessori school in Wörgl, Austria. The children and teachers excitedly explored the new materials like the Roman arch and the hundreds board, while watching Allison’s instructional videos on how to use them.

I arranged my mid-morning visits to the Garden of Flowers in time to observe the Montessori classrooms of the three teachers, Fatima, Nadia and Rohina, and their students in action. My first Saturday, I brought with me a big box of new Montessori materials donated by Allison’s friend and colleague from a Montessori school in Wörgl, Austria. The children and teachers excitedly explored the new materials like the Roman arch and the hundreds board, while watching Allison’s instructional videos on how to use them.

I spent time with the women teachers and administrator and cook, along with the two men staff. Theoretically they were not supposed to co-mingle, but we all felt comfortable sitting and discussing together, albeit behind the closed doors of the school. We all ate together, having joyful lunches alongside the brilliant and energetic children. These joyful kids were so happy to be together. After lunch, I spent time in the yard with them while they were playing. One long-time friend from the UN often came and shared lunch, and he donated some funds for outdoor play equipment.

It became abundantly clear that in the midst of the chaotic and concerning situation in the city and in the country, these children in the Garden of Flowers were thriving, writing and reading, constructing things and constructing themselves.

Again there was within me that mishmash of feelings, seeing the light-hearted, well-fed children in the Garden of Flowers, and then on the way back to my hotel seeing children in the streets dirty and begging. In my mind, I began to call these street children, “children without future”.

The very complex circumstances of the fabric of the society made me doubt that I could ever truly put the pieces together to express people’s lives, whether women, children or men, into one single narrative of today’s Afghanistan.

By Mostafa Vaziri

(Dec. 2024, Innsbruck, Austria)